Texas has grown a bumper crop of book authors and, with that, an ever-expanding list of literary festivals. San Antonio’s sprawls around its towering tomato-red public library every spring. Lubbock daringly throws its in sweaty August, while Boerne awaits the arrival of typically more bearable October weather. Then there’s the biggest of them all: the Texas Book Festival, which will gather some 250 authors in early November and erect a bibliophilic tent city out front of the state Capitol, perhaps ironically the launching pad of myriad political attacks on supposedly intolerable tomes and sinful librarians.

This year’s Austin fest includes a suite of authors whose work the Texas Observer has covered: Steve Harrigan, with Sorrowful Mysteries, his haunting “sideways memoir” meditation on Portuguese child mystics;Jim Harrington, who recently penned his account of building the Texas Civil Rights Project; and my own true Texas horror story, The Scientist and the Serial Killer.

The festival lineup adds plenty more to Texans’ 2025 must-read lists. Here are three featured nonfiction tales by Texas authors filled with intrigue, espionage, and previously untold backstories.

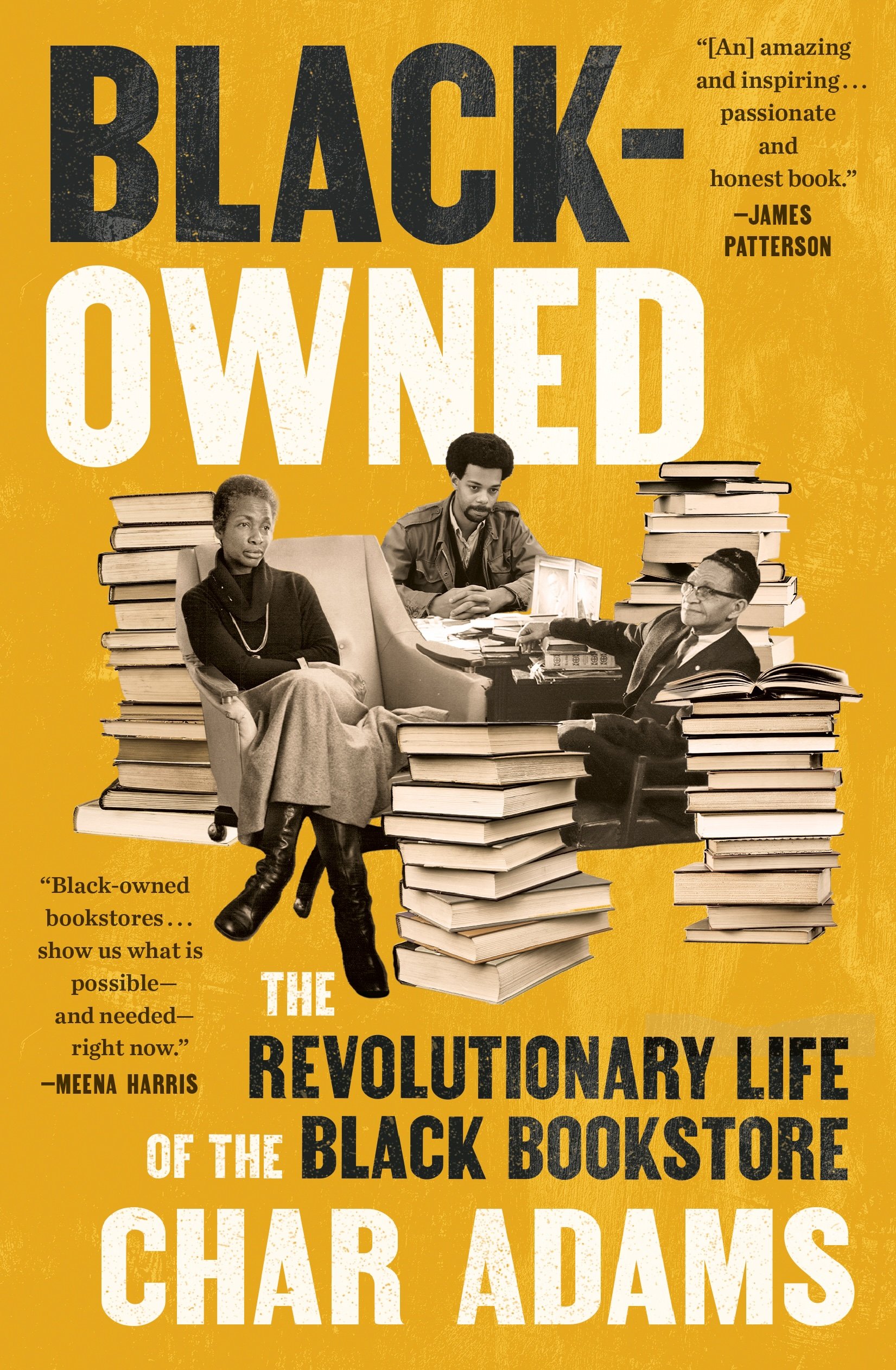

Black-Owned: The Revolutionary Life of the Black Bookstore by Char Adams. Tiny Reparations Books. November 2025

Black-Owned: The Revolutionary Life of the Black Bookstore by Char Adams. Tiny Reparations Books. November 2025Char Adams, until recently an NBC News correspondent in Dallas, has a background in edgy contemporary features: She previously worked for People magazine. But her first book takes a historical turn. It’s a compelling compilation of mini-profiles of many unsung heroes of America’s Black-owned bookstores, from a courageous pioneering abolitionist who ran his own store in the 1800s—surviving many attacks on his business and himself—to contemporary owners, like the two sisters who operate The Dock in East Fort Worth.

In each chapter, Adams delves deep into the owners’ biographies, philosophies, and roles, weaving a tapestry that crosses time and space.

“When I went into this project, I knew I had a really big responsibility—there were so many Black booksellers and historians who were and who are counting on me to tell the story right,” Adams told the Observer. “It truly is the first full-length book to chronicle the history of Black-owned bookstores in this country.”

Her book introduces us to many admirable men—and women. Many were pioneers who stood up for emancipation, civil rights, or (particularly in the 1970s) Black nationalism. They sold books that were banned or were simply unavailable elsewhere. They hosted speakers and events and joined local protests. Some died long ago, yet Adams rooted out their words through documents and brought them to life. There’s David Ruggles, the abolitionist who opened the nation’s first Black bookstore, in Manhattan in 1834, when he was sometimes targeted by runaway-slave catchers. And Lewis Michaux, who ran the African National Memorial bookstore in Harlem from the 1930s to the 1970s.

Adams tracked down and interviewed contemporary owners like James Fugate, of the celebrity-filled Los Angeles bookstore Isso Wan. And Emma Rodgers, a Texan whose Black Images Book Bazaar was born in 1986 from her own desire for more Black children’s books: As Adams writes, “She drove all over Dallas looking for titles with positive images of Black children to add to party favors for her son’s birthday in the late 1970s. Rodgers ultimately found them, but not without great frustration.”

Sadly, the stories of too many Black-owned stores ended after the shops were damaged or destroyed by looting, vandalism, and arson—in the case of one Detroit store, at the hands of local police. The FBI pops up in these pages for its monitoring of bookstore owners. Indeed, Adams’ book was inspired by an Atlantic article she read about “The FBI’s War on Black-Owned Bookstores” in the 1960s and ’70s.

“My interest was piqued in the sense that I wanted to know what that experience was like for booksellers personally,” Adams said. “So I started just tracking down those booksellers and talking to them and getting a vivid picture.”

Two Kansas couples whose bookstore was targeted weren’t politically active at all. “They just saw a need in their communities. They just saw that Black kids around them did not have a lot of access to books,” Adams told the Observer.

Adams trains a revealing new lens on American history and on the struggles of Black literary leaders. Each store’s success, as she writes, has relied in part on the owners’ courage, tenacity, and vision—and the faithfulness of its patrons.

Adams is particularly skilled at telling stories about American culture and history—from 2020 until March 2025, she covered race and identity for NBC.She witnessed firsthand how Black-owned bookstores saw business surge after shootings of young Black men by police, especially in 2020 after Houston native George Floyd was restrained and killed by Minneapolis police.

Even as she rushed to complete her research, Adams still frequented Black bookstores near her Dallas home, including the older Pan-African Connection and the Blacklit bookstore, which opened in 2022 in Farmers Branch. (Her book includes a list of U.S. stores and booksellers’ recommended reading.) To her, those two Dallas stores represent generational differences—the first being more spiritual and traditional and the second “a carefully designed event space”—yet she considers both “different branches of a single tree.”

Project Mind Control: Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA, and the Tragedy of MKULTRA by John Lisle. St. Martin’s Press. May 2025

Project Mind Control: Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA, and the Tragedy of MKULTRA by John Lisle. St. Martin’s Press. May 2025John Lisle, a mild-mannered University of Texas at Austin professor who specializes in the history of science, spends a lot of time in voluminous government archives tracking dark secrets that sound like conspiracy theories. He was busy reviewing records in the Library of Congress for his PhD dissertation when he stumbled on previously unpublished accounts of a top-secret CIA mind-control program—the subject of his new book.

Lisle already knew a lot about the odd life and strange career of Sidney Gottlieb, a shadowy scientist who led a program called MKUltra. Gottlieb oversaw mind-control experiments for about two decades that used an “exhaustive number of drugs” as well as hypnotism and myriad other techniques. But he’d largely evaded scrutiny, partly because he destroyed nearly all of his records in the 1970s.

In the archives, Lisle found sworn statements that he’d never seen published anywhere. His discovery of depositions from Gottlieb and other CIA figures allowed him to build compelling narratives about Gottlieb and MKUltra—and to disclose previously unknown information.

Some early CIA mind-control experiments were conducted (without permission) on government employees, including Frank Olson, a scientist dosed at a work gathering in Maryland who returned home “a totally different person,” according to his wife. The agency whisked Olson away to New York for emergency mental health treatment, but he threw himself out of a 13-story hotel window. An internal CIA investigation blamed Olson’s death on the flawed experiments, Lisle writes, yet they continued unchanged.

Olson’s family eventually sued and won a settlement. But Lisle’s discovery was of depositions in another lawsuit involving people who sued the CIA after being subjected to MKUltra experiments while incarcerated in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. As part of that case, an activist civil rights attorney grilled Gottlieb and other key CIA players.

Lisle found 823 pages of material, and he uses it to weave a narrative centered on the bizarre scientist: “From the defense’s perspective, Gottlieb’s depositions were a disaster. From the historian’s perspective, they’re a gold mine,” he writes.

Lisle’s book provides new details from insiders about how America’s mind-control program progressed. It eventually included about 149 subprojects conducted by scientists at mental hospitals, military bases, and safe houses. All were funded by CIA money laundered through shell companies and foundations. One redacted subproject list, eventually made public, suggests some experiments were conducted in Texas, possibly at the University of Texas and Texas Christian University.

The author describes some victims: Harold Blauer, a professional tennis player, who was killed during experiments conducted at the New York State Psychiatric Institute in 1953 and whose family received a settlement. And Jimmy Shaver, a 29-year-old father of two stationed at Lackland Air Force Base, who suddenly kidnapped, raped, and murdered a 3-year-old girl in a 1954 incident that he claimed not to recall. Shaver, who had no prior criminal history, was then examined before trial by Louis Jolyon West, the base’s resident psychiatrist, who had been conducting work funded under MKUltra around that same time.

Lisle devotes little space to allegations raised in another nonfiction book, CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties,by journalist Tom O’’Neill. O’Neill spent years investigating possible ties between Manson and the CIA’s mind-control program and postulated that Manson, a former federal prisoner, might have met West, who visited San Francisco as part of his LSD experiments. In an interview, Lisle expressed skepticism that Manson’s ability to order other “Family” members to kill could have been linked to the CIA’s conducting MKUltra experiments on him. Instead, Lisle suggested that West, the CIA researcher, could have been trying to learn from the cult leader’s techniques. “Manson was actually a lot better [than West] at manipulation,” Lisle told the Observer.

Lisle found only scant information about what happened to the many victims who received the bizarre treatments, including the former Atlanta Federal Penitentiary prisoners who sued the CIA. “I had a really hard time looking up people who were involved in this. It was difficult to find major figures, anyone involved with them, anyone who is willing to talk,” he told the Observer.

I couldn’t help but wonder: What else was in the files Gottlieb purged?

She Kills: The Murderous Socialite, the Cross-Dressing Bank Robber, and Other True Crime Tales by Skip Hollandsworth. HarperCollins. October 2025

She Kills: The Murderous Socialite, the Cross-Dressing Bank Robber, and Other True Crime Tales by Skip Hollandsworth. HarperCollins. October 2025Fans of Skip Hollandsworth, famed chronicler of true crime, will find much to love in this new collection of compelling narratives featuring the dark side of Texas womanhood. It includes many page-turning Texas Monthly features that I had never forgotten, including the 2007 tale of soft-spoken Vickie Dawn Jackson, the goody-two-shoes-nurse-turned-serial-killer dubbed the “Angel of Death” and the 2021 story of “The Notorious Mrs. Mossler,” a deadly high-society Houstonian.

Often, Hollandsworth uses his considerable skills to delve deep beneath the skin of the most complex and bizarre characters, and he frequently uncovers common ground and unexpected insights. He introduces Jackson to his readers, for example, explaining how carefully she tapped small-town resources to make herself pleasing to patients, including those she eventually killed. “Her hair, which she dyed herself at her kitchen sink with Lady Clairol Pale Blonde, would be neatly brushed and pulled back in a little knot on the top of her head—Vickie believed it was important that a nurse never let her hair get in the way of her work—and because she also thought that patients liked nurses who smelled good, she would be wearing a dab of Charlie on her neck, which she’d buy on sale at Wal-Mart.”

His ability to connect and convey folk in far-flung Texas is also apparent in his masterful “Midnight in the Garden of East Texas,” but that story’s disqualified for this collection given that the killer is male. (Fortunately, Richard Linklater made a film about Bernie.)

My favorite part of this story collection is the personalized notes that Hollandsworth uses to stitch it together. In the introduction, Hollandsworth shares how his fascination with crime began and his life changed in the summer of 1974, when he was a preacher’s kid and read about an unsolved crime in his hometown of Wichita Falls.

“When church members asked me what I planned to do when I grew up, I told them I would most likely become a Presbyterian pastor. … Then, on the morning of June 22, I walked into the kitchen and glanced at the local newspaper, the Wichita Falls Record News, that my father had brought in from the yard. Spread across the front page, in heavy two-inch-high block print, was the headline: Millionaire Oilman, Wife Found Dead; Couple Fatally Shot in Home Here.”

Throughout the rest of the book, Hollandsworth provides information on that case and other crimes he’s spent his life chronicling. Another standout tale is “The Fugitive,” his 2008 story about yet another nurse, Deborah Murphey, an apparently law-abiding wife and mother in East Texas who was suddenly arrested by out-of-state bounty hunters to the shock of her friends and neighbors. “‘The nicest lady in the world turned into an escapee from the law,’ marveled Linda Veitch, the owner of the town’s biggest beauty salon, the Hair Depot,” he wrote.

Hollandsworth’s investigation of Murphey’s unusual arrest revealed she’d been convicted of armed robbery as a teen more than three decades prior. She’d subsequently managed to escape from a Georgia prison, only after being repeatedly abused by a trio of guards. He found evidence of a broader culture of abuse of female prisoners in those years. An attorney who filed suit on behalf of other victims told Hollandsworth that several inmates had “mentioned [Murphey] and the abuse she had been forced to endure.”

That compelling tale became a game-changing investigation. Outraged readers contacted the governor’s offices in Georgia and Texas, creating a wave of support for Murphey. Ultimately, the Georgia Department of Corrections didn’t pursue extradition, and Murphey, according to Hollandsworth’s postscript, was able to continue her life as a law-abiding Texan.

Hollandsworth’s previous book, Midnight Assassin, chronicles an unidentified ax murderer—Austin’s own Jack the Ripper, a complex historic mystery that he investigated and told without being able to interview a single living witness. Still, I think Hollandsworth’s superpower is his ability to connect with people and get them to make surprising or even shocking admissions.

I’m hoping Hollandsworth’s next book is a memoir. I’d like to hear more about the lessons he’s learned as a Texas true crime writer and how his own life changed by forging deep connections with so many notorious, tragic, eccentric, and downright strange characters. Sometimes, as he told me, he winds up “inside their lives.”

For more Observer books coverage, see texasobserver.org/topics/books.

The post Black Bookstore Owners, Government Spies, and Murder appeared first on The Texas Observer.

(2).png)

1 month ago

74

1 month ago

74

English (US)

English (US)